Н.А.ХАН. К ВОПРОСУ О ПОНЯТИИ ДЕНЕЖНАЯ КУЛЬТУРА В АРХЕОЛОГИИ.

Сегодняшние добавление от 13,12,14. Любезность американского издательства, название которого в целях избежания обвинений в рекламе здесь не приводится, позволяет утверждать, что повторить или переоснастить приведенную ниже работу будет затруднительно. Спасибо.

Сегодняшние добавление от 13,12,14. Любезность американского издательства, название которого в целях избежания обвинений в рекламе здесь не приводится, позволяет утверждать, что повторить или переоснастить приведенную ниже работу будет затруднительно. Спасибо.

After invitation the article will be delete.

ON THE CONCEPT OF MONETARY CULTURE IN ARCHEOLOGY.

(In Russian below).

It is considered, that the “Archaeological Culture” (АC) concept could be extended as a concept which doesn’t apply to the so-called ‘class societies’, i.e. it correlates with prehistory. These class societies may be thoroughly examined, if the AC concept is singled out in the course of archaeological source studies.

One of the distinctive and prominent characteristics of human civilization is the availability of money and monetary circulation. It goes without saying that the more advanced the society is, the more complicated its monetary circulation becomes.

In prehistoric times, various objects, taken from the real world, were understood as money and commenced to be used for carrying out all sorts of transactions. In this case, it does not matter whether it occurred in the area of house economy, or at the tribal level or even in transcontinental trade. It does not mean that there was a commodity exchange based not on these principles, the principles of a monetary carrier.

The current monetary circulation is characterized by a certain set of monetary carriers, where mankind has arrived through a long evolution. It is known that the first paper Chinese money (10 century) is considered to be a certain stage on the way to the current payment system (like credit Cards).

Appearing at the opening ceremony of the 18th annual conference of the European Association of Archeologists (EAA) in Helsinki on August 29, 2012, ЕАА President Prof. Friedrich Lüth underlined the great value of archeological research devoted to paleo-economics of ancient societies.

Mankind has traversed long path on its way to money. The revelation of a certain type of a monetary carrier, its role in a historically formed system of monetary circulation in various ethnic groups, will invariably be of considerable interest. Therefore, for studying the periods of historical development of a certain epoch, it will be important to identify the peculiarities of monetary circulation, which, from the archaeological point of view, represents the identification of a set of those artifacts (assembled by J-C. Gardin), i.e. things and objects, which acted as monetary carriers. From here one can draw a

conclusion that “Monetary Culture” (MC) can exist chronologically at a later period of time than АC. And, to be exact, the MC concept can be used until the occurrence of current paper money.

The use of the denarius on periphery of the Roman empire made it possible to introduce the neighboring peoples to the civilized (at that time) monetary circulation — in Eastern Europe Byzantine’s solids began to substitute the Roman money. Byzantine’s solids got to Scandinavia with the help of the Slavs, which was one of the factors of such phenomenon as the “Viking Age” and contributed to the distribution of the Arabian dirham in Europe.

At the same time, the Arabian dirham was the most effective object in the real world, which is amenable to archaeological and numismatic procedures. Some estimations made by St. Bolin, R. Vasmer, K. Rasmussen, K. Ripsling, U. Linder-Welin, I. Gustin, Th. Noonan and Y.A. Pakhomov have allowed to reveal a number of parameters of the dirham spreading in Europe.

However, one has to remember the fact that the population of eastern Europe and the Russian Plain also used fur skins as a means of payment. It is a complicated question, which, however, is worthy of the definition, according to which monetary circulation cannot be based only on one type of monetary carrier. In that case, there were coins, vessels, furs, the Indian Ocean shells, beads, a spindle whorl of pink slate, etc. The role of each of the above carriers is still to be determined (Callmer J. 1977; Hingston-Quiggin 1970, Yanin 2009: 213).

Meanwhile it should be noted that a change in their proportions enables a researcher to obtain considerable historical data, which have not been reflected in scanty written sources.

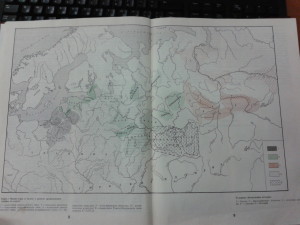

Even in the process of attributing toreutics of the vessels, found in the Russian empire territory, 1909, on the basis of the map-plotted data, according to V. P. Darkevich, two areas of their occurrence were noticed: the Kama and Ob basins. /Fig.1. 7/.

Fig.1. The first map of vessels found in Russia — Siberia (according to Ya. I. Smirnov).

Further overlaying on the map of object findings either connected, or capable of being connected to MC, as well as the local topography analysis, and the study of metrology of some of the findings, allow the researcher to state that the area of findings, in particular, in the Kama basin not only doesn’t coincide with the AC existing in that period, but also considerably surpasses its territorial coverage.

That made it possible to use, as a working scheme, the Viatsk-Kama Area (VKA) of findings of Oriental, Byzantian and Chinese silver, and Russian bullions, as a geomorphological basis for further research in the field of historical geography, which at the present time can be presented as Monetary Culture (MC)

MC exists in archeology both in a narrow, and in the wide sense. Any archaeological artifact, found in the process of archaeological works, which relates to monetary circulation, can characterize MC features of a certain ethnos, which bearers left one or another АC. But on the whole, thanks to V. F. Gening (1988, pp. 25-27), archeology uses the term ‘historical and geographical region’. In particular, the term is applied, where various АC co-exist, representing close ethnoses (Artamonov, 1971; Klein, 1998: 193). Such region is singled out in Prikamye (the Kama river region). /Fig. 2/.

![]()

Fig. 2. Ethnic map of the E.Europe- Ob region (VI-IX centuries) by «Archaeologia of USSR, 1987).

However, this region is geographically singled out as an area (VKA), possessing the whole set of material carriers of monetary circulation, represented by toreutics, Oriental coins, as well as by Chinese, Russian and Gold Horde bullions.

Therefore, one can draw a conclusion that MC of VKA can be seen as an independent and rather prestigious object of scientific analysis.

From the point of view of methodology, the above-mentioned scheme of the correlation between areas of types/cultures and a cultural group, suggested by D. Clark (1978: 311), allows to state more confidently the identification and correlation between АC and MC. /Fig. 3/.

Fig. 3. Scientific model of situational relations and cultural complexes in the systems of archaeological cultures (by D. Clarke).

The existence of VKA is dated from the period of 6 to 14 century.

The trade exchange, which took place at that time, was a rather complicated transaction from the point of view of political economics. It is worth mentioning that the exchange was made with furs supplied by the indigenous population.

In Western Siberia the basis of MC were silver vessels and furs. We will not pay attention to the fact that they were intended for foreign trade. A static character of the barter process finds acknowledgement on the American continent, when C. B. Wesson and M. A. Rees noticed that local tribes rejected more technologically advanced goods, thereby preserving their traditionally conservative shape of material and technological culture. (Wesson, Rees 1997: 112-113).

For example, the question has never been raised why Arabian coins were found in the Kama river region, whereas in the Ob river region there were none at all. In the same way as the question, what is the explanation of the occurrence of bronze Egyptian vessels, dated 6-7 cent., from the Thames upstream to the Danube upstream, as it is known from the work of J. Verner (1961: 564, 585-590). Most likely they did not affect monetary circulation in continental Europe, while here after Post-Roman triple-coins monetary circulation, gold coins, coined from the Byzantian sample from 580, were introduced, which is G. Williams’ newest deduction (2012: 150). It is worth mentioning that the Post-Roman influence was possibly related to political and economic development of Northern Europe (The Agrarian History 2011: 61).

In this connection, referring to Smirnov’s map, it is necessary to pay attention to the fact, that he was the first one to identify the area of the vessels occurrence within a square of the towns of Tomsk — Krasnoyarsk — Minusinsk — Barnaul. It should be added that in Siberia, archeologists still find objects of Oriental toreutics (Sokrovishcha Priobʹya -‘Treasures of Ob River Region’, 1996).

The above allows the researcher to look for an answer to the question on the possibility of the assumption of migrations from Malta to Siberia during the early paleolithic period, as it was suggested by A. P. Derevjanko (2006: 26), since in this case science has the established distribution center of the products of toreutics: Byzantium — Iran — Central Asia.

Knowing the contents of various hoards, like the Hoen hoard (9 century) from Norway — royal treasures of gold things and Arabian gold dinars (Fig. 4);

Fig.4. Hoen hoard (by J. Graham-Cambell, D. Skre).

Arkhangelsk hoards of 1989, and hoards of Sweden’s Kufic silver and especially, those of the island of Gotland, allowed us to essentially define the characteristics of separate MC components and to single out some backbone definitions.

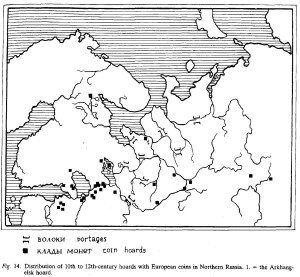

In particular, in publication about the Arkhangelsk hoard 1989, numismatist V. M. Potin carried out last to this day cartographical binding of hoards of the West European coins to the territory of northeastern Europe. /Fig. 5/.

Fig. 5. Map of hoards (10-12 cc). European coins in the North-east of Europe (by V. Potin).

Hoards of the West European coins of 10-12 centuries found in the territory of northeastern Europe, make it possible to assume a correlation with the data in the “Tale of Bygone Years” (Russia’s first chronicle) about the relations of colonial type between Novgorod and Perm.

The Vychegda river basin is the northern part of the territory of the big historical and cultural area known as Perm.

Perm is a Finnish word, which means ‘vagrant merchants’, “land on the outskirts”, “on the border”, “behind a village fence”.

Any further procedures of studying this MC are connected with the analysis of topography of the found artifacts, which represent a certain MC.

As you can see from the map, compiled by V.M. Ptonym, the boundary between different Money Cultures was the Ural mountains. Who was the «Zavolochye» later their N.A. Makarov did not pay attention to this circumstance, although criticized him before.

Monetary carriers collected as a result of the circulation process – money circulation in complexes, which are named “hoards” in numismatics, archeology and, consequently, MC. The Viking Age hoards were brilliantly attributed in M. Stenberger’s works and modern Sweden’s researcher Br. Härdh.

It should be noted that hoards not only reflect monetary circulation, but also show the processes of ‘money accumulation’. Thus, this term should be used for modern fixation of the historical events of monetary circulation, which reflect the facts of monetary history from another epoch and therefore, it is possible to draw a conclusion that hoards (sometimes called ‘deposits’ in numismatic literature) are monuments of monetary culture of a certain historical and geographical region, area, ethnos, etc.

Analyzing the concentration structure of monetary carriers within a hoard, attention should be paid to monetary components of the Arkhangelsk hoard, which has similarities with some other numismatic monuments.

The top part of coins in the hoard was pinpointed by researchers , where TPQ of German coins is dated from the last decade of the XI century. The German denarii inside the hoard are not mixed with the English coins, which chronologically form the top part. The top is dated from first quarter of 12 century (Nosov, Ovsyannikov, Potin 1992: 18-20).

The common archaeological procedure — revealing chronological complexes, makes it possible to speak confidently about a different source of the hoard origin, how coins got to the hoard area, which characterizes monetary culture of the Northern Dvina river area chronologically. At the same time, MC allows us to draw an analogy, considered below, taking into account spatial separateness of monuments to MC horizontal component.

E. N. Nosov as an analogy cites Kuolojrvi hoard, dated 1839 (Kuolojrvi Polar Circle), to the north from Helsinki, reconstructed by T. Tulvio. Basically they were the Frisian mintage coins, dated 3rd quarter of 11 century, which arrived to Lapland from Karelia and Northern Russia together with the English coins. However, on the other hand, Tulvio writes, that the greatest group of silver coins, 34% (German, Norwegian mintage, from silver of low denominations, dated the end of 11 cent.), arrived to Scandinavia from Germany. A.D.1100 became a chronological boundary. (Tulvio T 2002: 33 r., 34 r.). It was the Arkhangelsk hoard that helped us to fill a considerable gap in our knowledge, in which the top part was presented by the 12th century English coins, which is unique.

In this chronological cross-cut of the monetary source study, it is easy to see spatial connections of interaction of the revealed monetary culture of the North of Europe, and moreover, speaking the digital language, it has a ‘double expansion’.

It is possible to draw a conclusion that coins from the German cities arrived via the Dvina estuary to Novgorod, while the English coins arrived by sea, most likely with the help of Norwegian Vikings.

Vertical and horizontal structure of AC is considered by V. B. Kovalevskaya (1995: 100, 113; Klein 1998: 192).

Let us have an example demonstrating interactions of MC elements and complexes in a horizontal plane.

Proceeding from our conclusion that hoards containing denarii are characterized by tributary system relations, i.e. these are taxes which never reached Novgorod, then their contact with some other findings reveals some monetary centers in VKA. There are two such centers: one is around Cherdin, and the other is in the middle of the Chepets river, around the modern town of Glazov.

The Cherdin monetary center is connected not only with the European coins hoard, but also with the hoard of Arabian coins, vessels, in addition to female silver ornaments — grivnas, which Swedish archeologists and numismatists name the Perm type grivna /Fig. 6/.

Fig. 6. Multi-faceted fastener of the Perm type grivna. Silver. Photo.

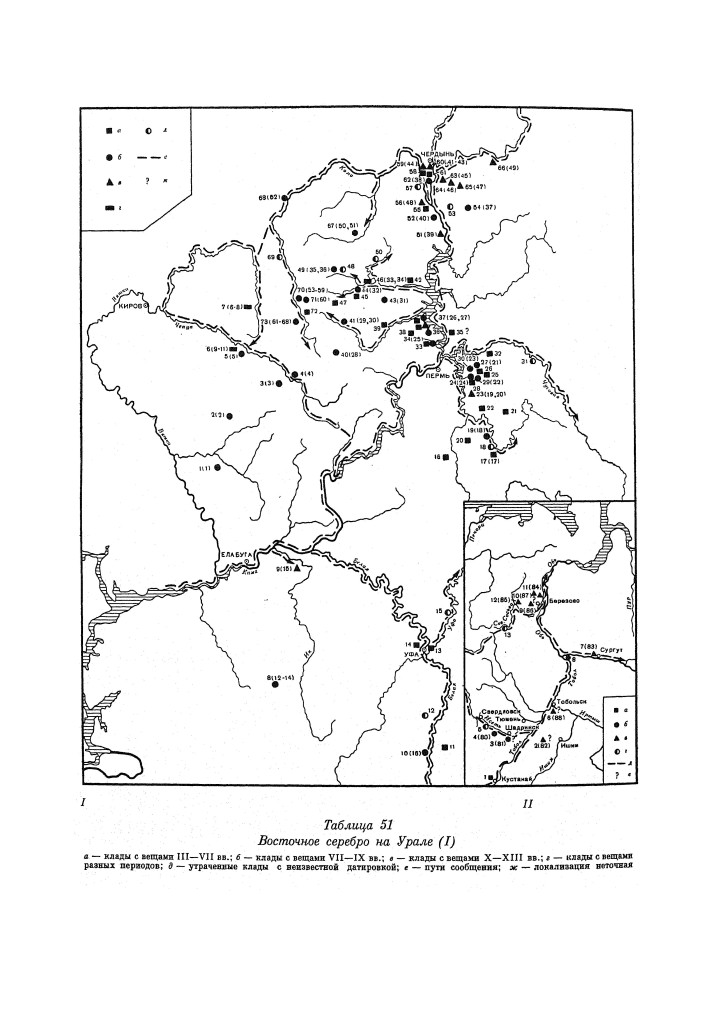

Apparently, this center /Fig. 7/ served as a starting point for the creation of the trans-European cultural and trading bridge, which archeologist G. S. Lebedev called a bridge from the Kama to Britain.

Fig. 7. Distribution map of Oriental silver on the Kama (V. Darkevitch).

Thus, MC is an archeological concept, the substantiated characteristic of monetary circulation in a specific geographic location during a certain historical period.

Precious and non-precious metal bullions constitute a material basis of monetary culture among artefact complexes.This theoretical approach to the organization of the material involves a mutch number of different cognitive procedures. At the same time, as part of a theory of modern archaeological researchers use the term—concept empiricism in order to highlight areas of source in the organization of archaeological material (Johnson 2001: 765).

In Egypt non-precious metal bullions were accepted by weight (Morgan 1965: 34). Special research of Italian numismatists was devoted to the study of historical and archaeological value of copper, bronze and brass bullions (Bronze Age, 14-12 cent. BC, Mediterranean basin: Cyprus-Sicily-Sardinia). The research was highly acclaimed by scientists (Harding 2011: 308-310).

Bronze bullions were found in the VKA hoards, dating middle of A.D. 1000. They were known during the Viking Age in the Circum-Baltic zone. |Fig. 8, 9/.

Fig. 8. Bronze bullions of Pre-Arabic time from VKA (according to R. Goldina).

Fig. 9. Bronze bullions found in Latvia (according to V. Urtans).

Apparently, these artifacts had no international value; they were used in order to maintain local MC, reflecting local MC (Muhamadiev 1990: 72-74, Table VII). It makes the archeological finding made at the well-known Earthen site of ancient settlement in Old Ladoga in 2002, under the direction of A. N. Kirpischnikov, where molds for casting bullions were found, more interesting. |Fig. 10/.

Fig. 10. Mold for casting bullions. Clay. Old Ladoga (by A. Kirpischnikov).

Certainly, this could not answer the question what metals were cast with its help. However, the comparison with the above illustration answers the question, which perfectly corresponds with the cultural tradition already established by archeologists – the tradition of ties between the population of the Volkhov river region and the Western Dvina valley, which was studied by J. Herrman, G.V.Vilinbahov.

Bullions of non-precious metals serve as the localization of local monetary circulation, which is prior to monetary circulation on the basis of objects made of currency metal. Hoards of non-precious metals (e.g. Galich Hoard in Spitsyn 1903, in which manufacturing tools and ornaments were hoarded) are not considered to be money hoarding. Hoards accumulation were mapped by archaeologists, particularly in Slovakia, including hundreds of axes, as well as jewelry-rings. Moreover, this accumulation is located very close to the locations of extraction of ore — Alps (Prehistoric Europe 2009 : 217 , fig.7.15). This should not distract us from the fact that the accumulation of bronze products, not related to monetary culture, are similar in their cognitive potential to the accumulation of seals of Polish Drogichin, which directly characterizes MC.

On the whole, we have deliberately directed your attention to the role of precious and non-precious metal bullions acting as monetary carriers. Having considerable distribution (sometimes called ‘monetary streams of bullions’), they are represented by such monuments as Hedebju, Birka, Kaupang, and Ribe. The researchers, who investigated these streams, are M. Stenberger, A. Attman, N. Bauer, N.Mayhew, J. Munro, Cr. Kilger, S. Sinbæk, A. Peterson, V. Potin and E.A. Pakhomov. All the above makes it possible to assert that “bullion-based monetary culture” can act as a specific direction in research. It also includes such undated and interpolated artifacts as jewelry, which presents considerable scientific problems for dating certain hoard complexes (Silver Economies 2011: 153-172. Graham-Campbell 1980: 111).

Symbols and signs are components of bullion culture. They act not only as elements of iconography, but also as property indicator as well as indicator of technological transformation in the Middle Ages.

N.P. Bauer noted that the bullions marked with an arrow and one lateral branch, as well as a trefoil on a fifty-kopeck coin of the Serpukhov hoard (Bauer 2011: 105, 189) had considerable diachronic parallels in Eastern Europe’s monetary issues. |Fig.11, 12/.

Fig. 11. Silver bullion from one of the of the Viking Age hoards in Latvia (according to Br. Härdh).

Fig. 12. Trefoil, late mediaeval Russia, numismatic data (according to A. V. Chernetsov).

In archeology MC occupies the second paleo-social level, which naturally proceeds from the first level — source study. If the data on the burial complexes reveals a layer of people, who were connected with money, then the functioning of money, even in a primitive form, is defined as a ceremonial action in sacralized places. Certainly, one should not forget about the thematic level of money at the interpretation level (Masson 1978: 76-83), which is of vital importance under the conditions of the absence of money, in the modern sense of this word.

In this regard, the use of the developed scheme for theoretical archeology, as J.-Сl. Gardin offered (J-Cl. Gardin — 1983: 63-69, Fig. 7; 201-204), where compilation — explication – interpretation, seems rather productive. It must be emphasized that this taxonomy reflects gnosiology of the studying process.

The example set by V. Masson (1978: 81) demonstrates how not to leave the archaeological context when studying such a polysystem problem as money. Ethnologists noted a case of using a huge and extremely heavy cobble-stone as a payment means in Micronesia. The transaction was considered to be done, when an agreeable inscription was made on the boulder, meaning that since given time the object belonged to given person, though the object never moved in space.

At the same time, the researcher fairly noticed that the object was not an archaeological source, and estimated it in terms of sociology as having just “prestigious value”. And it gives it a social context.

Certainly, it is obvious that the first operation, carried out on material carriers (money equivalents) is an archaeological procedure, (even close to studying the cultural heritage), whereas the second one is economic anthropology, widespread in the Paleo-Indian studying in the North American continent, in particular. It presupposes that paleo-economic reconstructions are connected with an ecosystem of paleolithic societies. This is an appreciable extension of the primary calculations of the quantity of grown barley, proportions between wild and domestic animals in a human daily diet, carried out by archeologists of Europe, the USA (Tankersley, Isaac 1990: 4-7. Karlheinz 1998: 38-40, fig.1-3. The Agrarian History 2011: 41-44, 69, tabl. 2.7. Guljaev 1979: 70-71).

Here one can use the term an “archaeological contract” in view of the fact that it is necessary to define where the archaeological source study is over, and where some other sciences take over. (Note 2. It’s pretty much picks up the social role of archeology as a science, allowing to determine the status and protection of the heritage, including the heritage of ethnic minorities (Lekberg 2007: 149, 155).).

The last statement has a big heuristic value, as it has recently been established by economic historians (on the basis of Malthus’ history), that in the Middle Ages a person needed two hundredweights of grain per year, which allows to explain the expansion of a colonized ecumene (JEH 2009: 896-897).

As is well known, unknown, little-studied phenomena and processes that archaeologists can not be understood and explained in terms of conventional thinking, we can understand and evaluate the cognitive, using modern ethnological parallels.

Anthropologists described a case in Africa when in order to receive some goods or services, they had to procure some other goods or services. V. L. Cameron, who continued D. Livingstone’s work, wrote:

“A curious currency is used here [Central Africa], everything is assessed in beads called ‘sofi’, something that looks like small pieces of broken pipe-stem. At the beginning of market-day, men with wallets full of these beads give them for a fee to people who are going to make a purchase; and when the market is closed they receive them again from the market people and make a profit on both transactions, after the manner of money-changers.»

Let us look at V. Cameron’s description of his attempts to procure a canoe to cross Lake Tanganyika, which is considered to be a textbook example.

“My first concern was to procure a canoe to sail across Lake Tanganyika. But owners of two canoes, promised to me by Syde bin Sadim, were away, therefore, I could not get them. However, I found a good canoe, which belongied to Syde bin Halib / …/) and managed to hire it from an agent, even though at an extortionate price.

The hire was arranged rather successfully. Syde’s agent wanted to be paid in ivory, which I did not have. But I found that Mohammed ibn Salib had ivory, and wanted cloth. Still, as I had no cloth, this did not assist me greatly until I heard that Mohammed ibn Gharib had cloth and wanted wire. Fortunately, I had it.

So I gave Mohammed ibn Gharib the required amount of wire, and then he handed over cloth to Mohammed ibn Salib, who in his turn gave Syde ibn Habib’s agent the requested ivory. Then he allowed me to have the boat.» (Cameron 1981: 172-173; 1877: Ch.14).

The above represents a classic example from economic anthropology, where as it is shown, it is impossible to consider one transaction isolated from the rest of them. In the present global world it will cause at least suspicions of tendentiousness if not a strong bias. One should not hide behind the well-known words of economic philosopher Friedrich Hayek that money becomes “inexplicable abstractions” in people’s minds. This is a direction of thought in economic anthropology, and here it will be enough to say that we can see a display of monetary civilization, since money is an attribute of civilization.

Let us pay attention to the interaction in terms of cross-monetary “asynchronous” relations between a contemporary (the traveler) and the primary source (African tribes). Describing his hardships in hiring a canoe, Cameron observed that, as an investor, he had more than once overpaid. These data co-ordinate with the direction of research developed by modern science: “There are two major differences. Firstly, the distinction between the two is blurred since there is no way of knowing whether the party who receives coconuts intends to consume them instead of using them as payment in later transactions”. (Silver Economies 2011: 70).

The above enhances cognitive possibilities of archeology, as is seen in the newest archaeological literature of American experts St. Falconer and Ch. Redman, who described the way how African tribes were engaged in distant transcontinental tusk trade, using slave labor. (Earle 2011: 321).

In his time G. P. Murdock (2003: 433; Murdock G. P. 1949) drew a conclusion that pro-austronesians had the social structure of a pro-hawaiian type, when this prototype seems, in his opinion, more ancient than the other types. Here political picture and monetary relations are of particular interest. Chronological synchronization of various forms of monetary relations is of considerable interest; it depends not only on natural factors, traditionalism, and degree of matrilocality, because in medieval Europe, as shown by Le Goff (2010: 162-163; ch.12), different types of money circulated in various social strata.

In modern global archeology trade is viewed as a social institution, which establishes connections and relations between distant communities and it is perfectly right not to study money and monetary relations in the «trade and exchange» topic. However, researches made it possible to identify a very important detail, leading us to the level of understanding of intertribal trade and exchange. It was also indicated, that trade in primeval period meant circulation, i.e. the circulation of goods (Social Archaeologies of Trade and Exchange 2010 : 29), where the money was not used . This means that there was the goods-gifts circulation, but not the circulation of money. After all, it is well-known, that one of the most important functions of money is a potential of circulation.

This circulation is shown on the example of market trade, where local money were used. They demonstrate the narrowness of the market rather than restrictions on entry into it.

It is interesting, that the findings of accumulations of same/similar to Chubukov-Sofi will represent a hoard, which can be studied archaeologically so numismatically.

In archeology hoards have a special value. According to researches of Br. Härdh, J. Graham-Campbell, S. M. Sindbæk and other authors in Europe, they reflect a diversity of formations, both in artifacts, and in metrology of things they are composed of. The Vjatsk-Kama Area hoards are filled with Byzantian oriental vessels, silver neck ornaments, bullions, as well as various amounts of Arabian coins; they present a reasonably good basis for studying the stratification of local societies. The data of preliminary metrological studies show the existence of both the local counting system and the Arabian coin-based system (Härdh 1996: 137. Khan 2009: 18-20).

It is useful to digress here and consider that 2009 Nobel Prize winner E. Ostrom, to substantiate procedural constructions, uses a synthesis of such mismatched terms as ‘prehistoric anthropology’ and ‘monetary theory’. Here it should be noted, that her empirical researches are arranged in a system of methodologically verified theoretical constructions. The development of some specific rules by some groups of people, including behavioral stereotype-based rules, cannot be substituted by the use of the others, and any change in the rules themselves is frequently institutional in nature (Ostrom 1991: 185-190). In this regard, the appeal of archaeologists towards methods of economics, when explaining the two kinds of trade — «by money» and «by barter», carries a strong charge of institutionality. (Social archaeologies of Trade and exchange 2010: 35)

In this context the use of economic anthropology terms is quite justified. Thus, ethnoarcheology can also get substantial material for studying the processes of paleo-economic reconstruction of ancient and prehistoric societies. On the whole, it is considered that economic anthropology has already singled out its basic attributes (Caraher 2011: 267-269. Sketches 1999, p. 5).

Returning to the turn of objects as the medium of circulation in prehistory, it is necessary to pay attention to functioning of the same «products» of the natural world in various civilizations. According to F. Braudel, in the territory of Western Sudan salt played the role of monetary equivalent. The well-known traveler, Livingstone’s follower, wondered whether it was in Ethiopia or Somalia that he “had bought a chicken for a piece of salt”.

At the same time, in the newest research of archeologists, who created a specialized colloquium on this subject (AAS 2011), and also in the works of British economic historian P. Spufford it is shown that salt as a commodity product arrived to Veliky Novgorod via merchants of the Hanseatic League from Lübeck (Spufford 2003: 298 map, 300). At the same time, the Galich salt in the northeast of Russia is well-known. However, the Galich salt never went to Novgorod, and, unfortunately, E. Rybina does not write about this fact (E. Rybina 2001:158). Although, it is a well-known fact that salt was the object of the law of succession in Vladimir Russia – see Dmitry Donsky’s will of 1389 (Horoshkevich 1963: 222-223).

Apparently, the assumption about procedures of payment for such strategic goods should be connected with the specific nature of the trading union, as well as with the cycle of salt extraction and/or its deliveries. Salt is a rather valuable commodity. It is the basis of pre-industrial chemical industry — soda, dyes, detergents, fertilizers – what is well-known even in ancient Egypt (AAS 2011: 163-167).

As a conclusive proof of this assumption, we will cite the reference made by Yu. S. Vasiliev (1971: 109, reference 52) to the “Tzar’s Charter to Dvina Customs Officials, dated 1588”. It is said there that the Novgorodians, being exposed to trading restrictions due to non-tariff regulations, were imposed to a four-denga tax rate per ruble when purchasing/selling salt, whereas the usual tax rate was just two dengas (Acts … 1889: 408-409).

Flashback: 1383, the Novgorodians, under the archbishop’s banner, got to the Vychegda river, where they were defeated by the Ustyug and Perm people near the town of Soldor (currently Solvychegodsk). They got there via «high latitudes” (Davidov V. N, Florya B. N; Ovsyannikov O. V; Martin J.; Kollmann N., Bulatov V. N.; Khan N. А.). The question is whether the Novgorodians simply wanted to win back the town of Perm or that the military campaign was the implementation of their desire to take over the mineral resources, about which we know from some later sources (Gritskov 2003: 38-39).

Since ancient times, salt has been a daily ration of both people and, and domestic animals, and, moreover, nearly in the same proportions (AAS 2011: 127-128, 147-148). According to E. Kluge and A. Averyanov, in the 14 century, the population of Novgorod was 24,000 — 35,000 people and, having added here the similar number of domestic animals, it is easy to estimate the amount of salt, which Novgorod needed – at 500 tons per year (not counting the amount of salt required for preservation of fish, meat, and pickles). A cyclic recurrence of this process was an additional workload for importers – it led to instability of prices (AAS 20011: 125).

Therefore, the presence of English gold coins (nobles) in Novgorod, and Ivan III-minted coins, dated 2nd half of XV century (Potin 1970: 101-105; Shiryakov: 1993), makes it possible to assume that gold currency was used as payment for salt.

In the same way, black peppercorn is known to have been used as monetary currency in Europe, whereas some other agricultural plants were used as monetary currency in some other societies (Threlfall — Holmes 2001: 153-157; Shokhin 1988: 4-5, 282, references 3, 5; 26, 280). Thus, the same commodity in different and distant civilizations, which existed at the same time, was used in different ways. The study of functioning of these civilizations makes it possible to reveal differentiated aspects of monetary culture manifestation.

In order to avoid possible errors, connected with the attribution of money as circulation carriers, and also circulation of any other carriers, it is necessary to single out metrology, monetary calculation, and also accounting money. A local resident of eastern Europe of the Viking Age never cared what was written on Arabian or German coins — anyway weight parameters of monetary circulation were always of paramount importance (‘Silver Economies’ Bauer).

B. M. Serrano and G. C. Andreotti observed in their latest research: “How these messages were understood by the local, basically illiterate, population is unknown to us. Thus, we should bear in mind this logic restriction”, when we consider a particular coin iconography, whether belonging to the Hellenistic epoch, or to the late Middle Ages (Serrano, Andreotti 2012: 2. Chernetsov, 1983).

In MC metrology-defined weight norms were presented by specific monetary units, having specific face value. But counting and some weight data did not always correspond to specific face values. This particular circumstance singles out money from the rest of real and monetary world. When money is not presented by a specific face value, but expressed metrologically, in this case this money has a counting character. To reveal this character is an important and considerable concern of numismatics in the MC field. This procedure is the level of abstraction from the bustle of idle things.

Thus, archeologists should not be worried that historical and economic theory considers money as a neutral thing. However, separating MC artefacts from an archaeological complex is feasible, taking into account some peculiarities of money functioning in a certain social medium, as an archetype of material culture.

Therefore, based on calculations, it was to possible to single out the Genoese libra (sottili) in Alexandria, Genoa, Caffa in the Crimean peninsula and Pera (Constantinople), weighing 316.75 grams (Hinz W., 1955: 32-33), as well as the Moscow grivna weighing 196.2 grams (Khan 2009: 88-89). The above face values had no carriers, i.e. they were not presented by numismatical artifacts.

But, due to the fact that calculations were made with their help, one can assume that they served as an anti-inflationary tool. At that time, inflation was not called ‘inflation’, but it always took a different form, and in bookkeeping entries it had an registered character (Le Goff 2010: 99-100: Ch. 7-8; Volcraft 2011: 15; Han 2011: 159). Therefore, the calculating character of money should be understood in the sense of accounting control over money supply, and not in the sense of counting specific carriers: money, paper money, medals, tokens, bullions, and coins.

Earlier we have mentioned that we presumably know about two MC components of the population of Western Siberia connected, as it was shown in the above works, with foreign trade — Bulgar, Central Asia, China, Novgorod, and Scandinavia. But this conclusion became possible only as a result of operating with such concept as MC (Khan 2011: 163).

The analysis of synthesis of maps and charts /Fig.2, 4, 6/- /Fig.13/.

Fig.13. Historical and geomorphological map of the Vychegda river basin and the Kama. X-XIV centuries.

Legend. Border: 1 — VKA, 2 — Lands Visu / Isu & Perm, 3 — Volga Bulgariy. 4 — Magna Hungaria.

Ethnoterritory: 5-Mari. 6 — Udmurt. 7 — Komi Zyrians. 8 — Komi-Perm. 9 — Luza permtsa.

Hatch: areas of distribution: 10 — Cervical hryvnia Permian (Glazov) type. Hoards with numbers — around Glazov, without numbers of Cherdyn. 11 — Vymsky AK. 12 — Lomovatov rodanovskaya-AK. 13 — Chepetskaya AK. 14 — Yurtikovskaya AK. 15 — Kocherginskaya AK.

The above shows that to the west of the Urals, there was a culture based on bullions and coins. The fact led to the conclusion that beyond the Urals, some other monetary culture existed, not coin-based. However, it would be too straightforward to consider the non-availability of the Arabian dirham there as a MC peculiarity. The thing is that the coin was not required in the Ob river basin in terms of MC. Besides, it was not required for the silver traffic to Scandinavia either, which was provided with a monetary stream through Russia, currently studied by the European science (Muller-Wille 2009; Silver Economies: Tulvio 2002. Carelli 2001. Bogucki 2004). At that particular time display/ingot transition economy became widespread in Scandinavia, which was based on the silver arriving from the East (Silver Economies 2011: 34).

With the help of MC it is possible to continue pursuing scientific research. A formidable challenge to political history of eastern England during the Viking Age is the formation and interaction of such institutes as the power and the church. Recognizing the fact that coins reflect the state sovereignty, they, as it is shown below, reflect the sovereignty of the power itself. /Fig. 14/.

Fig. 14. Penny of King Cnut (by D.Rollason).

This is a reference to coins with King Cnut the Great on the observe and a cross on the reverse (Rollason 2003: 226-227; Malmer 1997: 143, 271, 548-567). The synergy interacting process between the church and the Viking King power could explain the most complicated political and ideological interference taking place in England’s society in early X century.

The above-mentioned corresponds to the already known statement of historiography regarding the question when “a change of the system happened due to barbarian intrusions mainly by the taking tribal leaders and soldiers into the ruling class, and manorialism (seigniorial system of liege relations – N. Khan) received its ‘definitive’ stamp in the VIII and IX centuries, during the time of Saracens, Vikings and Hungarian invasions, when this became the economic basis of the feudal system.”(Cameron, Neal 2003: 45-46, fig.3-1).

Chasing itself could well occur in York, which actually relates to the urban culture on G.Williams (2012: 152), whereas in England there was a transition to the introduction of the gold coins with the inscription LONGVIN.

We have shown cognitive potential use of these coins, which is a subsidiary of historical discipline, involves the study of monetary circulation in ancient and medieval times, based on coins and bars. Currently, the question of monetization in the Middle Ages, its extent, when «In societies with a high level of monetization, the parties would more often than not have had to counted their coins by number» (Gullbekk 1992: 103-104).

Get it now popular contemporary archeology or areology today implies taking into account the lost, as well as donated coins left by parishioners during their visit to the church, as it tried to H. Klackenberg (1992. p.64) on the example of Sweden. Interest in this kind of research increases the correlation of these data with those of other areas, such as church archeology.

The suggested method of arranging the material, and cultural system D. Clarke’s cultural system cited here, allow us to pay even greater attention to horseshoe-shaped fibulas with a many-sided head, where some of them had images of a cross. Silver fasteners found in hoards /Fig. 15, 16/ leave no doubt that they are elements of monetary culture, and their decor was brought to Karelia by Scandinavians (Härdh 1996: 115, 136. Fig. 30. Kochkurkina 2004: 130-133; 150; 152).

Fig.15. Horseshoe-shaped fibula from the Rauto hoard, Karelia. Photo by Br. Härd.

Fig. 16. Fibula from the Sipilanmaki hoard, Karelia (according to S. I. Kochkurkina).

Certainly, the MC concept will be further developed and specified. But it is possible to assume that the MC borders coincided with neither the specified АC, nor ethno-geographical areas. MC is assumed to be like an independent historical and geographical region.Areals AC does not coincide with the ethnic territories and DC area identified may not be the same, and often does not coincide with the territories of ethnic groups and ranges AC. Last sentence is based on the culture of bars in the monetary circulation of medieval Europe mentioned above here.

The above shows the way of interaction between archeology and paleo-economics in studying ancient societies. Notably, the specific material with its problematic and chronological aspects was demonstrated by the scientists of Great Britain, and Sweden(Archaeological Theory 2012: 35).

As we have tried to show here, the study of MC passes through the deployment of an empirical model of the functioning of MC in the structure of archaeological research.

Fig. 17. The model of studying Monetary Culture (MC). 1 — Material structurization; 2 – Data explication; 3 — Interpretation.

One should bear in mind, that on the point of view of a researcher discoverer, singling out certain artifacts is related to the “cluster” of monetary culture (e.g. Drogichin seals or glass bracelets), and it is necessary to attribute them, so that colleague researchers and future historiography, would have less doubts concerning the competency of such attribution.

Summing up, the MC as the epistemological potential of theoretical knowledge is a cognitive learning tool archaeological sources in the system of scientific concepts of commodity-money relations and exchange and related activities of other objects of the material world.

In fact, MC — The organization of a particular archaeological material within their own ideas about the researcher of commodity-money relations in the studied them locus specific era.

Thus MK — complex of archaeological sources, organized in the framework of specific scientific concepts historically verified hronlogicheskih and territorial limits that characterize the commodity-money relations and related phenomena, processes and procedures of everyday life and studied ancient societies. Objects of the material world, studied and received within the framework of the archaeological study is the element base MC.

Therefore, the study of Money Culture, the peculiarities of its functioning, and mutual interference will contribute to some further scientific researches and provide as a contribution to the creation of archaeological theory.

Bibliography.

AAS — Archaeology and Anthropology of Salt: A Diachronic Approach. Proceedings of the International Colloquium.1-5 October 2008. Al. I. Cuza University (laşi. Romania). Ed.by M. Alexianu, O.Welter, R.-G. Сurcã // BAR Int. Series 2198. 2011.

Callmer J. Trade beats and trade bead in Scandinavia ca 800-1000 A.D. Malmo. (Acta archaeologia ludensia. Series in 4°. Nr 11). 1977. – 230 p.

Cameron R., Neal L. A concise economic history of the World. From Paleolithic Times to the Present / Fourth edition. N.Y.; Oxford: Oxford University press, 2003. 464 p.

Chernetsov A.V. Types on Russian Coins of the XIV and XV Centuries. An iconographic study / BAR International Series. 167. Oxford, 1983. 191 p.

Clarke David L. Analytical archaeology / Second ed. N.Y.Columbia univer. press., 1978, 484 p.

Earle Timothy. /Review/. St.Falconer, Ch.Redman, eds. Politics and Power: Archaeological Perspective on the Landscapes of Early State (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2009, 277 pp. // European Journal of Archaeology, 2011, Vol. 14. N.1-2. P.320-322.

Grierson Ph. Monete Bizantine Italia dal VII all‘ XI secolo // Moneta e scambi nell’alto medioevo [Texte imprimé] : [Lezioni e discussioni tenute in occasione della VIII Settimana di studio svoltasi a Spoleto] 21-27 aprile 1960 / Centro italiano di studi sull’alto medioevo Publication : Spoleto : Presso la sede del Centro, 1961. P.35-55.

Graham-Campbell J. The Viking World. London; Linkoln: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980.

Gullbekk S.H. Norway: Commodity Money, Silver and Coins // Silver Economiy… 2011, p.93-112.

Hinz W. Islamiche masse und gewichte ungerechnet ins metrishe system. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1955. 66 s.

Härdh Br. Vikingelizeitelishe deportfunde aus sudschweden. Probleme und analisen. Bonn – Lund, 1976. 176 s.

Härdh Br. Siver in the Viking Age. A regional-economic Study Stockholm: Aitmqist & Wiksell International, 1996. 222 p.

Harding A. /Review/. Fulvia Lo Schiavo, James D. Muhly, Robert Maddin and Alcssandra Giumlia-Mair, eds, Oxhide Ingots in the Central Mediterranean (Biblioteca di Antichita Cipriote 8, Rome: A. G. Leventis Foundation and CNR — Istituto di Studi sulle Civilta dclI’Egeo e del Vicino Oriente, 2009, 519 pp.// EJA. 2011. V.14. N.1-2. P.308-310.

Hingston-Quiggin A. A survey of primitive money. The beginning of currency. L.: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1970. 344 p.

JEH 2009 – Llebowitz J. J. /Review/. A History of World Agriculture: From the Neolithic Age to the Current Crisis By M. Mazoyer and L. Roudart. Translated by James H. Membrez. London: Earthscan, 2006. Pp. 528. // The Journal Of Economic History. 2009, Vol.69. Numb.3. P.896-897.

Johnson M.H. On the nature of empiricism in archaeology // Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.). 2011, Is. 17, 764-787.

Caraher W. Ya. Hamilakis and A. Anagnostopoulos, eds, Archaeological Ethnographies (Pubic Archaeology 8/2-3) (Cambridge: Maney Publishing, 2009,322 pp. // JEA.2011.Vol.14. N.1-2. P.267-269.

Karlheinz St. Climatic fluctuations and neolithic economic adaptations in the 4th millennium ВС: Case Study from South-West Germany // Papers from the EAA Third Annual Meeting at Ravenna 1997. Vol. I: Pre- and Protohistory. Edited by M. Pearce & M. Tosi. BAR International Series 717. P.38-44.

Klackenberg H. Moneta nostra : Monetarisering i medeltidens Sverige. — Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell intern, 1992.

Lekberg P. Making it matter: towards a Swedish contract archaeology for social sustainability // Quality Management in Archaeology. Ed.by W.J.H.Willems, M.H. van den Dries. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2007. — VIII, 164 p.

Nosov E.N., Ovsyannikov O.V., Potin V.M. The Arkhangelsk Hoard // Fennoscandika, Helsinki. 1992. IX., p.3-21.

Malmer B. The Anglo- Scandinavian coinage c. 995-1020. Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Letters History and Antiquities, 1997. — 635 р.

Morgan E.V. A history of money. Balt. — Maryland: Pengium Books, 1965. 240 p.

Muller-Wille M. Ünzfunde Der Frühmittelalterlichen Handelssiedlungen Von Ribe, Hedeby und Kaupang // Великий Новгород и средневековая Русь. М., 2009. С.455-467. (На немецком языке).

Ostrom Elinor. Governing the commons. The evolution of institutions for collective action. Camb.: Camb. Un.Press, 1991. 282 p.

Pearce S. The archaeology of South West Britain. London: COLLINS St James’s Place, 1981.

Pegolotti, — Francesco Balducci Pegolotti. La practica della Mercatura. Cambridge-Massachusetts: The intelegencer printed Go, 1936. 443 p.

Rollason D. Northumbria, 500-1100. Creation and Destructions of Kingdom. Camb. Cambr.Univer,press, 2003.

Silver Economies, Monetization and Society in Scandinavia, AD 800-1100

Edited by J. Graham-Campbell, S. M. Sindbæk and G. Williams. Aarhus,

Aarhus University Press. 2011.

The Agrarian History of Sweden: From 400BC to AD2000. Edited by J. Myrdal and M.Morell. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2011. Pp. 336.

Spufford P. Power and profit the merchant in Medieval Europe. N.Y.: Thames & Hudson, 2003.

Tankersley K. B., Isaac B. L. /Editors/ . Early paleoindian economies of eastern North America. A Research Annual. Supplement 5 • 1990. Greenwich, Connecticut, London: Jai Press Inc.

Threlfall-Holmes M. Durham Cathedral Priory’s Consumption of Imported Goods: Wines and Spices, 1464-1520 // Revolution And Consumption In Late Medieval England / Ed. By Michael Hicks. — Woodbridge; Rochester: The Boydell Press, 2001, p.141-158.

Serrano B.M., Andrcotti G.C. Ethnic, cultural and civic identities in ancient coinage of the southern Iberian peninsula (3rdС. ВС-1-е. AD) // The City and the Coin in the Ancient and Early Medieval Worlds Edited by F. L. Sànchez / BAR International Series 2402. 2012. P. 1-16.

Silver Economies 2011 — Silver Economies, Monetization and Society in Scandinavia, AD 800-1100 / Edited by James Graham-Campbell, Søren M Sindbæk and Gareth Williams. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2011.

Tulvio T. The coins of the Kuolojarvi (Salla) hoard // Finnoscandia archaologica. II, 1985. P.31-35.

Urtans V.A. Senakie depoziti Latvija (lidz 1200 g). Riga: Zinatne,1977. 284 s.

Verner J. Fernhandel und Naturalwirtschaft im Östlichen Merowingerreich nach Archäologiscen und numismatischen // Moneta e scambi nell’alto medioevo [Texte imprimé] : [Lezioni e discussioni tenute in occasione della VIII Settimana di studio svoltasi a Spoleto] 21-27 aprile 1960 / Centro italiano di studi sull’alto medioevo Publication : Spoleto : Presso la sede del Centro, 1961. P.557-618.

Volcraft O. The Influence of Information Costs on the Integration of Financial Markets: Northern Europe,1350-1560. Institute of Economic History, School of Business and Economics, Humboldt-Universitat zu Berlin, 2011. 68 s.

Wesson C. B., Rees M.A. Between Contacts and Colonies. Archaeological Perspectives and Prehistoric Southeast. Tuscalossa & London: The Alabama Univer.press, 1997.

Williams G. Towns and minting in northern Europe in the early Middle ages // The City and the Coin in the Ancient and Early Medieval Worlds. Edited by F. L. Sànchez / BAR International Series 2402. 2012. P.148-159.

Акты, собранные в библиотеках и Архивах Российской Империи Археографическою экспедицию Императорской Академии Наук. Т.1 1889. С.408-411.

Артамонов М.И. Археологическая культура и этнос // Проблемы истории феодальной России. Сб.статей к 60-летию проф.В.В. Мавродина. Л.: Изд-во Ленинградск.ун-та, 1971. С.16-32.

Васильев Ю. С. Об историко-географическом понятии „Заволочье» // Там же, с.103-109.

Гарден Ж.-К. Теоретическая археология. М.: Прогресс, 1983.

Генинг В.Ф. Этническая история Западного Приаралья на рубеже нашей эры. М.: Наука, 1988. 240 с.

Голдина Р.Д. Древняя и средневековая история удмуртского народа. Ижевск: Изд-й дом ―Удмуртский университет. 1999. 464 с.

Гофф Ле, Жак. Средневековье и деньги. Очерк исторической антропологии. СПб: Евразия, 2010. /Goff Le J. Le moyen Age et l’Argent:/.

Гуляев В.И. Города-государства майа. М.: Наука, 1979.

Деревянко А.П. Миграции, конвергенции, аккультурация в раннем палеолите Евразии // Этнокультурные взаимодействия в Евразии: в 2 книгах / Ответ.редакторы А.П. Деревянко, В.И. Молодин, В.А. Тишков. Книга 2. М.: Наука, 2006. С.25-47.

Камерон В.Л. Пересекая Африку. / Перевод с английского Л.Е. Куббеля. М.: Наука, Гл.редакция восточной литературы, 1981 (Cameron Verney Lovett. Across Africa. London, 1877).

Кирпичников А.Н., Ениосова Н. В. Литейные формы для производства слитков из Старой Ладоги // Восточная Европа в Средневековье = К 80-летию Валентина Васильевича Седова : [Сборник статей]. — Москва: Наука, 2004. С. 290 – 296.

Клейн Л.С. Археологическая культура: теоретический анализ практики (Вместо рецензии /В.Б. Ковалевская/) // Сов.археология. 1998. № 1. С.187-193.

Ковалевская В.Б. Археологическая культура: практика, теория, компьютер. М., 1995.

Кочкуркина С.И. Народы Карелии: история и культура. Петрозаводск: Карелия, 2004. 208 с.

Массон В.М. Экономика и социальный строй древних обществ. М.: Наука, 1978.

Мельникова Е.А. О юридическом статусе готского двора в Новгороде в середине XIII в. // Великий Новгород и Средневековая Русь. М., 2009. С.95-102.

Мердок Дж.П. Социальная структура. Перевод с английского А.В. Коротаева. М.: ОГИ, 2003. /Murdock G.P. Social Structure. N.Y. – L.: Free Press, 1949.

Мухамадиев А.Г. Древние монеты Казани. Казань, 1990.

Потин В.М. Корабельники на Руси // Нумизматика и эпиграфика. Т.8. М., 1970. С.101-107.

Очерки экономической антропологии. М.: МГУ.1999. 128 с.

Рыбина Е.А. Торговля средневекового Новгорода. Историко-археологические очерки. Вел.Новгород: НовГУ им.Ярослава Мудрого, 2001. 390 с.

Сокровища Приобья / Отв.ред. М.Б. Пиотровский. СПб: Формика, 1996. – 228 с.

Толочко П.П. Киев – центр феодального землевладения на Руси X-XIII вв. // История народного хозяйства и экономической мысли Украинской ССР. Вып.15.1983. С.81-86. (На украинском языке).

Фёдоров-Давыдов Г.А. /Рецензия./. David L. Clarke. Analytical archaeology. L., 1968, 484 p. //

Сов.археология. 1979. № 3. С.258-274.

Хан Н.А. Историко-географические реалии Северо-восточной Европы и проблемы средневековой вятской истории [Научное издание]. М. – Киров: ООО «Типография «Старая Вятка», 2009. 214 с.

Хан Н.А. Послесловие составителя / Н.П. Бауер. Слитки серебра и золотые слитки русского средневековья. М.: Б.и., 2011. 221 с.

Хорошкевич А.Л. Торговля Великого Новгорода с Прибалтикой и Западной Европой в XIV—XV веках. М.1963. 222-223

Шохин В. К. Древняя Индия в культуре Руси (XI- середина XV в.). Источниковедческие проблемы. М.: Наука, 1988.

Янин В.Л. Денежно-весовые системы и очерки истории денежной системы средневекового Новгорода. М., 2009. — 416 с.

iiustration have subm 07.12.14. 17-26MSK 17th number

Н.А.ХАН

К ВОПРОСУ О ПОНЯТИИ ДЕНЕЖНАЯ КУЛЬТУРА В АРХЕОЛОГИИ.

Считается, что понятие «Археологическая культура» (АК) может быть распространено как понятие не относящиеся формационно к так называемым классовым обществам, т.е. соотносится с доисторией. Данные общества блестяще изучаются через выделение в процессе археологического источниковедения в понятие АК.

Одной из отличительных характерных особенностей человеческой цивилизации является наличие денег и денежного обращения. Естественно, что чем более продвинутой является тот или иной социум, то сложнее должно быть и денежное обращение.

In prehistory следует под деньгами понимать предметы, выделенные из вещного мира, которые стали использоваться для проведения каких-либо сделок-транзакций. В данном случае неважно будь то это в сфере домашних хозяйств, или на уровне межплеменной, даже трансконтинентальной торговли. Это абсолютно не означает, что существовал товарный обмен, основанный не на этих принципах – принципах денежного носителя.

Современное денежное обращение характеризуется определенным набором денежных носителей, к которому человечество прошло через долгую эволюцию. Известно, что первые бумажные китайские деньги 10 века являются определенными этапом на пути к современным платежным системам типа Cards.

Выступая на церемонии открытия 18-й ежегодной конференции Европейской ассоциации археологов в Хельсинки 29 августа 2012, Президент ЕАА, проф. Friedrich Lüth подчеркивал важное значение исследований археологов, посвященные палеоэкономикам древних обществ.

На пути к деньгам современности человечество прошло большой путь, что выявление того или иного типа денежного носителя, его роль в исторически определенной системе денежного обращения в самых различных этносах будет представлять всегда значительный интерес. Поэтому для изучения периодов исторического развития той или иной эпохи важно будет выделение особенностей денежного обращения, что с археологической точки зрения представляет собой выделение набора тех артефактов (assemble by J-K.Garden), т.е. вещей и предметов, которые выступали в роли денежного носителя. Отсюда сделаем вывод о том, что “денежная культура” (MC) может существовать хронологически в более позднее время, нежели АК. И, если быть точным, понятие MC можно использовать до появления современных бумажных денег.

Использование денария на периферии Римской империи позволило приобщить соседние народы к цивилизованному в то пору денежному обращению — в Вост.Европе на смену римским деньгам пришли византийские солиды. Именно они, посредством славян попали в Скандинавию, что послужило одним из факторов такого феномена как «эпоха викингов» и распространение арабского дирхема в Европе.

В тоже время Арабский дирхем был наиболее эффектным предметом вещного мира, хорошо поддающийся археологическим и нумизматическим процедурам, а некоторые подсчеты, проведенные St.Bolin, R.Vasmer, K.Rasmussen, K.Ripsling, U. linder-Welin, I.Gustin &Th.Noonan позволили выявить ряд параметров его распространения в Европе. В то же время необходимо вспомнить, что население восточной Европы и Русской равнины использовано в расчетах также шкурки пушных зверей. Это сложный вопрос, который впрочем достоин того определения, согласно которому денежное обращение не может быть основано только на одном типе денежного носителя. Здесь были и монеты, и сосуды, и меха, и раковины с Индийского океана, бусы, пряслица из розового шифера и т.д. роль каждого из перечисленных носителей ее предстоит установить (Callmer J. 1977; Hingston-Quiggin A., 1970, Янин 2009: 213). Между тем, что сейчас важно, отметить изменение их соотношения позволят, получить значительные исторические данные, не отраженные в скудных письменных источниках.

Еще в процессе атрибуции торевтики — сосудов, найденные на территории Российской империи в 1909 на основании данных, нанесенных на карту, было получено, согласно В.П Даркевичу,,2 области их распространения: бассейн р.Кама и Оби. /Fig.1. 7/.

Fig.1. Первая карта находок сосудов в России — Сибири (по Я.И.Смирнову).

Дальнейшее наложение на карту находок предметов, связанных или могущих быт связанными с MC, а также анализ локальной топографии и изучение метрологии некоторых из них позволяют констатировать, что ареал находок, в частности, в бассейне реки Кама не только не совпадают с существовавшими в тот период АК, но и заметно превосходит по территориальному охвату.

Последнее позволило в качестве рабочей схемы использовать определение Вятско-камский ареал выпадения восточного, византийского, китайского серебра, русских денежных слитков в качестве геоморфологической основы для дальнейших исследований в области исторической географии, and in present time может быть представлено как Money of culture (MC).

MC в археологии существует как в узком смысле, так и в широком. Любой археологический артефакт, найденный в процессе археологических работ, имеющий отношение к денежному обращению может характеризовать ту или иную сторону MC определенного этноса, насельники которого оставили ту или иную АК. Но в целом в археологии благодаря В.Ф. Генингу (1988, с.25-27) применяется термин историко-географического региона, в частности, где сосуществуют разные АК, представляющие близкие этносы (Артамонов 1971; Клейн 1998: 193). Такой регион выделен в Прикамье./Fig.2/.

Fig.2. Ethnicmap VI-IX cent.of Volga — Ob region (by R.Goldinа).

Но этот регион географически выделен как ареал (VKA),

имеющий в составе денежного обращения весь комплекс тех материальных носителей данного обращения, представленный как торевтикой, восточными монетами, китайскими, русскими и золотоордынскими слитками.

Поэтому, представляется, что CM VKA может представлять самостоятельный и весьма престижный объект научного анализа.

В методологическом плане вышеприведенная схема соотношения ареалов типов и культур с культурной группой, предложенная Д.Кларком (1978, р.311), позволяет уверенней констатировать выделение и соотношение АК и CM. /Fig.3/.

Fig.3. The scientific model of situational relations cultural complexes in the systems of archaeological cultures (by D.Clarke).

Существование VKA датируется периодом с 6 по 14 вв.

Производившийся обмен весьма сложное точки зрения политэкономии действо. Остановимся только на том обстоятельстве, что торговый обмен шел на меха местного автохтонного населения.

Здесь в западной Сибири основу MC составляло серебряные сосуды и меха. Сейчас мы не будем обращать внимание на то, что они предназначались для внешней торговли. Статичность самого процесса товарообмена находит подтверждение на американском континенте, когда C. B. Wesson and M. A. Rees заметили, что местные племена отвергают более технологические передовые товары, консервируя тем самым традиционно-консервативный облик материальной и технологической культуры. (Wesson, Rees 1997: 112-113).

Подобные данные накапливались как бы внутренне и не выводились, как говорится, на принтер.

Например, вопросов даже не возникало, почему на Каме были арабские монеты, на Оби их нет совсем. Точно также, как вопрос чем объяснить распространение бронзовых сосудов из Египта 6-7 вв. от верхней Темзы до верхнего Дуная, известные, в частности по работе J.Verner (1961: 564, 585-590). Наверно, они не влияли на денежное обращение в континентальной Европы, тогда как здесь после постримского triple-coins денежного обращения произошло введение золотых монет, чеканенных по византийскому образцу, начиная с 580 г., что следует новейшим обобщениям G.Williams (2012: 150). Учтем, что постримское влияние вероятно имело отношение к политическому и экономическому развитию северной Европы (The Agrarian History 2011: 61).

В этой связи, нельзя не обратить внимание, обратившись к карте Смирнова, что им впервые выделано также область распространения сосудов, заключенная в квадрате городов Томск – Красноярск — Минусинск – Барнаул. Добавим, в Сибири до сих пор находят предметы восточных торевтов (Сокровища Приобья 1996).

Приведенное вполне на уровне организации знания позволяет поискать ответа на вопрос о возможности предположения миграций с Мальты в Сибирь в эпоху раннего палеолита, что предположил А.П. Деревянко (2006: 26), поскольку в данном случае наука располагает установленным центром распространения изделий торевтики: Византия — Иран – Центральная Азия.

Знакомство с материалами кладов, таких как Hoen 9 в. из Норвегии – королевский клад золотых вещей и арабских золотых же

Fig.4. Hoen hoard (by J,Graham-Cambell, D.Skre).

динаров (Fig.4), а также Архангельского кладов 1989 г., и памятуя о кладах куфического серебра Швеции и особенно, острова Готланд, позволило нам существенно продвинуться в характеристике как отдельных составляющих MC, так и позволить выделить системообразующие определения.

В частности, в процессе публикации Архангельского клада 1989 г., нумизмат В.М. Потин осуществил последнюю на сегодняшний день картографическую привязку кладов западноевропейских монет, на территории Северо-востока Европы./ Fig.5/.

Fig.5. Map hoards 10-12 centuries. European coins in the Northerneast of Europe (by V.Potin).

Клады западноевропейских монет 10- 12 вв., найденные на территории северо-востока Европы, позволяют сделать предположение корреляции с данными Повести временных лет (Первая русская хроника- летопись) об отношениях колониального типа Новгорода и Пермью. Бассейн р.Вычегды – эта северная часть территории большой историко-культурной области известная как Пермь.

Пермь – финское слово означает бродячих торговце, земля на окраине, за-рубежом, на границе, за околицей.

Дальнейшие процедуры по изучению данной CM связаны с анализом топографии находок артефактов, представляющую ту или иную MC.

Как видно, из карты, составленной В.М.Птоным, границей между разными денежными культурами являлся Уральский хребет. Проводивший в Заволочье несколько позднее свои исследования Н.А.Макаров не обратил внимания на данное обстоятельство, хотя его и критиковали.

Денежные носители, собранные в результате процесса обращения – кругооборота денег в комплексы, которые в нумизматике, археологии и, как следствие, MC, следует называть кладами. Из блестящую атрибуцию времени викингов известны по работам М. Стенбергера и современной шведской исследовательницы Br.Härdh.

Сейчас представляется, что клады не сколько отражают денежное обращение, сколько показывают процессы накопления и данный термин употребим скорее с целью современной фиксации событий истории денежного обращения, отражающие ушедшие в иную эпоху факты денежной истории, и следовательно, можно сделать вывод о том, что клады, именуемые иногда в нумизматической литературе как депозиты, являются памятниками денежной культуры того или иного историко-географического региона, ареала, этноса и т.д.

Выясняя структуру концентрации денежных носителей в составе клада, обратим внимание в связи с анализом структуры такого накопления на монетную составляющую Архангельского клада, имеющему к тому же аналогии в других нумизматических памятниках.

Верхние части монет клада четко выделены исследователями, где TPQ немецких монет датируется последним десятилетием XI в. Германские денарии не перемешаны здесь с английскими монетами, которые образуют хронологически верхнюю часть, Она естественно имеет обособленную датировку – 1-я четв.12- в.(Nosov E.N., Ovsyannikov, Potin 1992: 18-20). Обычная археологическая процедура – выявление хронологических комплексов позволяет уверенно говорить о разном источнике происхождения, поступления монет в район выпадения клада, характеризуя денежную культуру местного низовьев Сев.Двины в хронологическом разрезе. MC вместе с тем, позволяет отнести рассматриваемую ниже аналогию, учитывая пространственную отдельность памятников к горизонтальной составляющей MC.

Е.Носов в качестве таковой приводит клад из Куолоярви 1839 г.(Kuolojrvi Polar Circle), к северу от Хельсинки, реконструированный Т.Тульвио (Tulvio T.). Монеты 3-й четверти 11 в.фризской в основном чеканки поступали в Лапландию из Карелии и Сев.Руси, куда входили и английские монеты. Однако с другой стороны, пишет Тульвио, наибольшая группа монет немецкий, норвежский эмиссий самого конца 11 в. серебра младших номиналов, составляет 34 процентов, поступала в Скандинавию из Германии. Хронологическим рубежом стал 1100 год (Tulvio T. 2002: 33 спр., 34 спр.). Здесь существенную лакуну знаний помог преодолеть Архангельский клад, в котором кроющая часть, что уникально, с 12 в.представлена английскими монетами.

В данном хронологическом срезе денежного источниковедения нетрудно видеть пространственные связи взаимодействия выявленной культуры денег (MC) Севера Европы, причем говоря цифровым языком, имеющее «двойное расширение».

Можно сделать вывод, что монеты германских городов поступили устье Двины через Новгород, а монеты английские — морским путем, скорее всего посредством норвежцев-викингов.

Вертикальная и горизонтальная структура АК рассматривается В.Б. Ковалевской (1995: 100, 113; Клейн 1998: 192).

Приведем пример проявления взаимодействий элементов и комплексов MC в горизонтальной плоскости.

Поскольку мы сделали вывод о том, что клады денариев характеризуют даннические отношения, т.е. это подати, которые не дошли до Новгорода, то их соприкосновение с другими находками говорит о каких-то денежных центрах в VKA. Таких – 2. Это вокруг Чердыни и на ср.Чепце, вокруг современного г.Глазова.

С чердынским денежным центром связаны не только находки клада европейских монет, но и клады арабских монет, сосудов, не говоря уже о серебряных женских украшениях – гривнах, которые шведские археологи и нумизматы называют гривнами пермского типа /Fig.6/.

Fig.6. Многогранная головка гривны пермского типа. Серебро. Фото. Fig.6. The multi-faceted fastener of Permian type hryvnia. Silver. Photos.

По-видимому, этот центр |Fig.7/ служил отправной точкой для создания трансъевропейского культурно-торгового моста, о котором археолог Г.С. Лебедев говорил как о мосте от Камы до Британии.

Fig.7 . Карта распространения восточного серебра на реке Кама (by V.Darkevitch).

Таким образом, MC – понятие археологии науки, овеществленная характеристика денежного обращения в тот или иной исторический период на конкретном географическом локусе.

Среди комплексов артефактов, составляющие материальную основу денежной культуры, заметное значение имеют слитки из драгоценных и недрагоценных металлов.

В Египте слитки из недрагоценных металлов принимались на вес (Morgan 1965: 34). В специальном исследовании итальянских нумизматов получили четкую историк-археологическую атрибуцию медные и бронзовые, а также латунные слитки бронзового века 14-12 в.до н.э. Cредиземноморья: Кипр-Сицилия-Сардиния, получившие соответствующие научное признание (Harding 2011: 308-310).

В кладах VKA найдены бронзовые слитки середины I тыс.н.э.. В циркумбалтийской зоне они известны в эпоху викингов |Fig. 8, 9/.

Fig. 8. Бронзовые слитки доарабского времени из VKA (по Р.Голдиной).

Fig.9 . Бронзовые слитки, найденные в Латвии (by V.Urtans).

Данные артефакты не имели как видно международного значения, они использовались в целях обеспечения локального MC, отражая собственно местные MC (Мухамадиенв 1990: 72-74, tabl.VII). Тем интересней археологическая находка, сделанная на знаменитом Земляном городище в Старой Ладоге в 2002, под руководством А.Н. Кирпичникова, когда были обнаружены литейные формы для отливки слитков |Fig. 10/.

Fig. 10. Литейная форма для литья слитков. Глина. Старая Ладога (by A.Kirpischnikov).

Разумеется, что данная форма не дает ответа на вопрос слитки, какого металла здесь отливались по большей части. Но сравнение с вышеприведенной иллюстрацией дает ответ на поставленный вопрос вполне соотносящийся с уже установленными археологами культурной традицией – традицией связей населения Поволховья с долиной Зап.Двины, что изучалось еще J.Herrrman.

В целом мы специально заострили внимание на роли слитков из драго- и недрагоценных металлов, выступающих в роли денежного носителя, поскольку имея значительное распространение, называемое иногда как денежные потоки слитков, представленные памятниками Хедебю, Бирка, Каупанг, Рибе так по авторам, исследующие потоки данного артефакта – M.Stenberger, A.Attman, N. Bauer, J.Munro, Cr.Kilger, S.Sinbæk, A.Peterson, V.Potin что позволяет вполне определиться со специальным направлением в исследовании как «денежная культура на основе слитков». Сюда же следует отнести также недатированные интерполировано такие артефакты как ювелирные изделия, составляющие в совокупности значительные научные проблемы для датировки тех или иных кладовых комплексов (Silver Economies 2011 :153-172. Graham-Campbell 1980: 111).

Составной частью культуры слитков как археологического определения могут быть символы и знаки не только выступающие как элементы иконографию, но и как имущественный показатель и показатель технологических трансформаций в средневековье. Отмеченные еще Н.П. Бауэром слитки со стрелкой с одной боковой веткой, а также трилистник на полтине Серпуховского клада (Бауер 2011: 105, 189) имеют значительные диахроннные параллели в денежном деле Восточной Европы. |Fig.11, 12/.

Fig. 11. Серебряные слитки из одного клада Латвии эпохи викингов (по Br Härdh). Fig. 7. Silver bullion from one of the Viking Age hoards in Latvia (by Br Härdh).

Fig.12. Трилистик по нумизматическим данным позднесредневековой Руси (по А.В. Чернецову).

MC в археологии имеет второй палесоциологический уровень, плавно вытекающий из первого источниковедческого. Если по материалам погребальных комплексов выделяется прослойка людей имеющих отношение к деньгам, то само функционирование денег пусть в первобытной форме определяется как обрядовое действие в сакрализованных местах. И конечно, не стоит забывать о тематическом уровне выделении денег на уровне интерпретации (Массон 1978: 76-83), что особенно важно у условиях отсутствия денег как таковых, т.е.в современном смысле денег.

В этой связи, использование развернутой схемы, для теоретической археологии, предложенной J.-Сl. Gardin (Гарденом Ж.- 1983: 63-69, Fig.7; 201-204), где компиляция – экспликация – интерпретация, выглядит весьма продуктивными. Подчеркнем, что данная таксономия отражает гносеологию процесса изучения.

Как не позволить себе выйти из археологического контекста в изучении столь полисистемной проблемы денег показывает пример, приведенный В.Массоном (1978: 81). В Микронезии отмечен этнологами случай использования в качестве средства расчета огромный неподъемный булыжник и сделка считалась совершенной при нанесении на нем соответствующей надписи, означающей, что с такого-то времени этот предмет принадлежит такому-то, при этом сам предмет в пространстве не перемещался. Вместе с тем, справедливо замечает исследователь, данный предмет не является археологическим источником, оценивая его в социологическом плане как «престижную ценность».

Конечно, следует отделять «зерна от плевел», поскольку очевидно, что первая операция на материальные носители-эквиваленты денег – есть археологическая процедура, (где-то даже изучение в рамках культурного наследия) тогда вторая — скорее экономическая антропология, получившая распространение в частности в палеоиндоведении североамериканского континента. Она предполагает полеэкономические реконструкции, связанны с экосистемой палеолитических обществ. Это заметное углубление первых подсчетов количества выращенного ячменя, пропорций диких и домашних животных пищевого рациона осуществляемое археологами Европы, США (Tankersley, Isaac 1990: 4-7. Karlheinz 1998: 38-40, fig.1-3. The Agrarian History 2011: 41-44, 69, tabl.2.7. Гуляев 1979: 70-71).

В этой связи уместно употребление термина «археологический контракт», ввиду того, что следует определить, где кончается археологическое источниковедение, а где начинается иная наука.

Последнее замечание имеет большое эвристическое значение, поскольку как недавно установлено экономическими историками на основе мальтузианской истории, человеку было необходимо в развитом средневековье 2 центнера зерна в год, позволяющие объяснить расширение колонизуемой ойкумены (JEH 2009: 896-897).

Далее.

Как ивзестно, неивезтсные, слабоизченные явления и процуессы, которые арехологами не могут быть поняты и объяснены в рамках привычных представлений, можно понять и когнитивно оценить прибьегая к анализу современных этнологических параллелей.

Антропологами описан случай в Африке, когда для того, чтобы получить тот или иной товар или услугу, приобретали иной и другой товар или услугу. В. Л. Камерон, продолживший дело Д.Ливингстона, описал, в частности как:

«Здесь в ходу, — читаем мы записки путешественника, — любопытная валюта: все оценивается в бусинах, именуемых софи. Это нечто напоминающее, по виду небольшие кусочки сломанного трубочного чубука. В начале базарного дня мужчины с кошелями, полными этих бус, раздают их определенную плату людям, желающим совершать покупки. А когда торжище закрывается, они вновь получают плату, теперь уже от базарных торговцев, и извлекают прибыль из обеих операций по методе, принятой у менял».

Далее без разрыва как опция В.Камерон описывает поиск лодки для переправы через Таньгаику, считающийся хрестоматийным.

«Первой моей заботой было добыть лодку, чтобы отправиться в плавание по Таньгаике. Но владельцы двух лодок, обещанных мне в Уияньенби Саидом Бен Садимом, были в отъезде, а поэтому получить эти лодки я не смог. Однако я нашел хорошую лодку, принадлежащую Саиду Бен Халибу /…/) и сумел ее нанять у его агента, хоть и за грабительскую цену.

Наем этот был организован довольно удачно. Агент Саида пожелал, чтобы ему платили слоновой костью, каковой у меня не было. Но я узнал, что у Мухаммеда Бен Салиба слоновая кость имеется, а он нуждается в ткани. Но и ткани у меня не было, так что это не слишком мне помогло, но я узнал, что ткань есть у Мухаммеда Бен Гариба, которому нужна была проволока. К счастью, она у меня была.

Итак, я передал Мухаммеду Бен Гарибу требуемую сумму в проволоке, после чего он передал ткань Мухаммеду Бен Салибу, который, в свою очередь, передал агенту Саида Бен Хабиба запрошенную им слоновую кость. После этого агент разрешил мне взять лодку.» … (Камерон 1981: 172-173; 1877: Chp.14).

Приведенное представляет собой пример из экономической антропологии, где, как представляется, нельзя одну транзакцию рассмаривать в отрыве другой, иной, третьей. В нынешнем глобальном мире это вызовет по меньшей мере подозрения в тенденциозности, если не сказать предвзятости. Не следует также прикрываться известными словами экономического философа Фридриха Хайека о том, что деньги в головах людей – “неизъяснимые абстракции”. Это направление в эконмчиеской антроплогии, и здесь же достаочно будет сказать, что мы можем видеть проявление формы денежной цивилизации, коль скоро деьнги явются атрибутом цивлизации.

Позволим себе обратить вникание на взаимодействие в плане кросс-денежных «асинхронных» отношений современника – путешественника и первоисточника – племен Африки. Камерон описывая мытарства по аренде лодки, замечал неодкратно, что переплатил, как инвестор. Эти данные вполне согласуется с направлением разысканий, вырабатываемых современной наукой: «There are two major differences. Firstly, in between the two is blurred since there is no way of knowing whether the party who receives coconuts intends to consume them instead of using them as payment in later transactions» (Silver Economies 2011: 70).

Приведенное повышает познавательные возможности археологии, как показано в новейшей археологической литературе американскими специалистами St.Falconer, Ch.Redman племена Африки широко занимались дальней трансконтинентальной торговлей бивнями, используя для этого труда рабов. (Earle 2011: 321).